Should we be rating and ranking schools?

School and district report cards were released in mid-September to little fanfare because they lacked state test scores. These scores form the heart of the report cards, but were missing from this year’s reports because the coronavirus pandemic shut down schools and prevented spring testing. Typically, these annual accountability reports lead to a few weeks of news stories on the ups and downs of district and school letter grades as compared to prior year results. Nearly as predictable as the hand-wringing by policy makers and politicians over low scores is the annual ritual of a story (like this one from 2016) linking these grades to poverty levels within schools and districts.

Maybe this year provides an opportunity to stop and think about a couple of questions related to the report cards. Questions such as, what do the report cards tell us about schools? And, should we be rating and ranking schools?

A Tale of Two Schools

Perhaps we should first examine if the ratings help the public differentiate between schools that are doing a good job of educating kids and those that are not. On its face, this may sound simple. Schools with more A’s are better schools. Except, it’s not that simple, but most people stop at this surface level analysis.

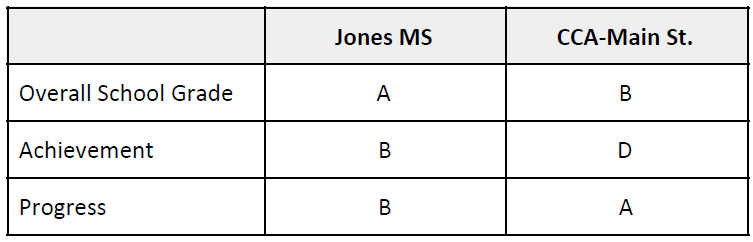

It may help here to zoom in and examine the data from two schools located in Columbus, Jones Middle School in Upper Arlington City Schools and Columbus Collegiate Academy-Main St. (a United Schools Network school), a public charter school located in the Near East Side neighborhood. Both schools serve grades 6-8 and are located less than 10 miles apart.

Jones Middle School has the better overall grade, and clearly outpaces CCA on the Achievement dimension of the report card. But in the Progress category, which measures how much growth students make during the school year, CCA earned an A to Jones’ B. This means that a high percentage of students at Jones begin the year on grade level (as indicated by higher percentages of proficient students in the Achievement category), but don’t grow as much as the students at CCA once there. This difference between Achievement and Progress grades becomes even more interesting as you factor in school and neighborhood characteristics.

School & Neighborhood Context

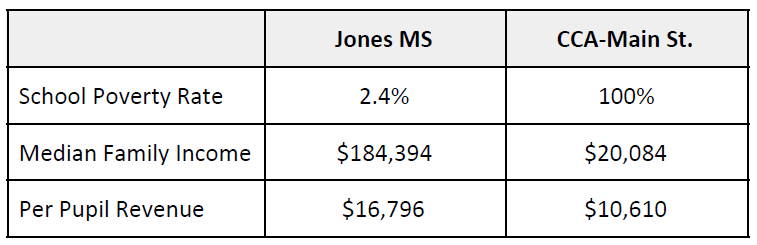

Inside the schoolhouse, an interesting picture emerges. Whereas Jones serves a student population that is 85% white, CCA serves a population that is 95% students of color. Both schools serve a similar portion of students with disabilities, but 100% of the students that attend CCA are economically disadvantaged as compared to the 2.4% served by Jones. Other report card measures such as attendance and chronic absenteeism tip heavily in favor of Jones. They have a 97.1% attendance rate and just 1.9% of their students are chronically absent. Compare this to the 93.2% attendance rate and 21.3% chronic absenteeism rate at CCA. However, framed in terms of the deep poverty of the community surrounding CCA, these numbers take on a different meaning. They are indicators of inequity in the form of housing instability, neighborhood violence, lack of access to healthcare, etc. as much or probably more than they are an indicator of school performance. As you examine these issues you quickly realize that the students at CCA are just as capable as the students at Jones, but many face overwhelming obstacles related to poverty.

Outside the schoolhouse, additional analysis is warranted as well. The median family income in the census tract within which Jones Middle School sits in Upper Arlington is $184,394. In the neighborhood surrounding CCA, the median family income is just $20,084. These inequities in neighborhood context and family resources are grounded in complex historical causal systems, but they are compounded by school funding disparities that are grounded in present day policies. Case in point, the per pupil revenue at CCA is $10,610 as compared to the $16,796 at Jones. Jones has almost no students living in poverty, and yet enjoys more than $6,000 in additional revenue per student than those that attend CCA. This funding inequity contributes to a whole new set of challenges for CCA when it comes to paying for a facility, paying teachers a competitive salary, and paying for core and extracurricular educational activities.

Systems Thinking

So, what are report card grades measuring exactly? Are those grades a fair representation of the activities occurring within the schoolhouse walls? Or, can a significant portion of those grades be attributed to the larger context in which a school sits. Systems thinking assigns most differences in school performance to the system and not to individual schools. One way to consider the theory behind the systems thinking perspective is to try to solve the following equation:

If A + B + C + D + E + F = 71 (Performance Index score), what is the numerical value of F?

Obviously, the equation cannot be solved without knowing the values of A through E, or at least their sum. However, the report card system in Ohio suggests that we can assign a value to F (the school) with no knowledge of the values or effects of the other variables. The accountability system accomplishes this impossible task a follows:

The Way Forward

Despite everything I’ve written here, I am a believer in accountability systems. I’m in favor of administering state tests that are standards-aligned and reported annually to the public. Understanding how students are performing on grade level standards is useful information. However, extending the accountability system to include the grading, rating, and ranking of schools is a misuse of this information from my perspective. Too much of the rating and ranking can be attributed to the system as opposed to being directly assignable to a school that sits within that system. As any reasonable person would conclude, and as illustrated in the comparison between Jones Middle School and Columbus Collegiate Academy, we have a long way to go to ensure that schools, and the students that attend those schools, are on equal ground upon enrollment. Our time would be better spent figuring out how to make this happen rather than on the constant re-calibration of inherently flawed school and district report card systems.

***

John A. Dues is the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter-management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus. Send feedback to jdues@unitedschoolsnetwork.org.