Appreciation for a System

The System of Profound Knowledge was developed by W. Edwards Deming across a lifetime of improvement work. It provides a map of theory by which to understand the organizations that we work in. The theory has four parts that interact to form the science of improvement: (1) Appreciation for a System, (2) Knowledge about Variation, (3) Theory of Knowledge, and (4) Psychology.

The aim of this month’s post is to describe the Appreciation for a System component.

Defining Appreciation for a System

Appreciation for a System quite literally means that we step back and see the organization we lead as a system. Dr. Deming recognized that organizations are characterized by a set of interactions among the people who work there, the tools, methods, and materials they have at their disposal, and the processes through which these people and resources join to accomplish its work.[1] This is the essence of a system. In my experience, systems leaders fall short of this appreciation most commonly in two areas. First, we overemphasize the extent to which problems can be attributed to individual educators as opposed to the underlying system. Second, we often fail to appreciate the idea that improvement in one area of our school system can lead to a decline in performance in the system as a whole.

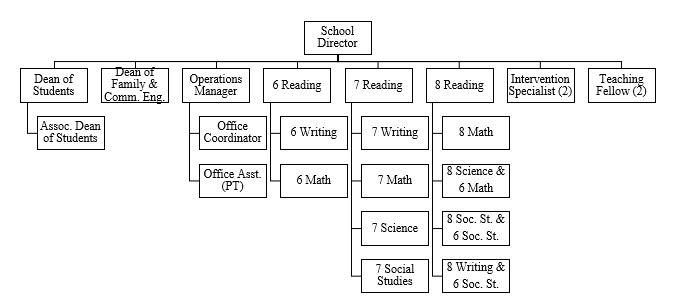

If you asked the typical school leader to show you their organizational structure, what would be produced would most likely look very much like Figure 1. It shows the 2018-2019 organizational chart for one of the middle schools at United Schools Network.

Figure 1. USN Middle School Organizational Chart (2018-2019)

When this is the picture you have in your head when asked about the structure of your organization, it is only natural then that when developing improvement plans you would almost exclusively focus on attempting to improve the people within the organization. This is what schools do when confronted with problems, they turn to professional development to improve the individual practice of teachers and administrators. However, despite spending billions on professional development activities in the United States, well-regarded studies by organizations such as the American Institutes for Research (AIR) and TNTP show no measurable results from this spending. This was the case even when the training was considered rigorously aligned to the tenets of best practice for educator professional development.[2]

Underappreciation for Systems

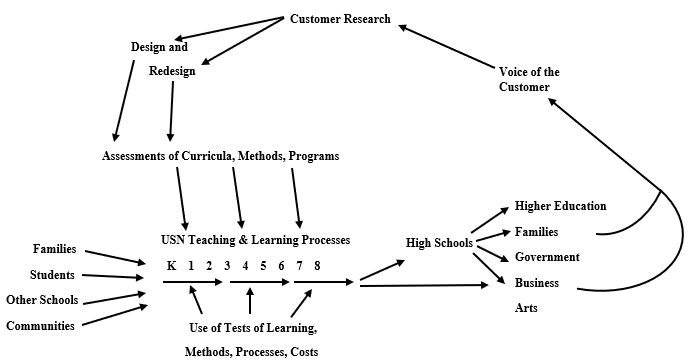

I would contend that an underappreciation for systems and their complexity lies at the heart of this issue. After studying Deming’s work in this area, I learned that one of the first things he taught the Japanese upon his arrival there in 1950 was that Japan must see itself as a system. A very different image begins to emerge when you view schools as a system, as do possibilities for improvement. That same middle school whose organizational chart was displayed previously is reconfigured in Figure 2 through a systems lens that I adapted from a diagram Deming displayed on a chalkboard in Japan.[3]

Figure 2. USN Middle School: A Systems View

A Systems View

Viewing the USN middle school as a system as displayed in Figure 2 opens numerous possibilities for improvement beyond simply working to improve the individuals who work in the school. In fact, it would be far more productive to work to improve the system in which the people work rather than solely focusing on the individual educator. To do this it is helpful to see, understand, and improve the larger system in which the school operates. Deming stressed the following:

I should estimate that in my experience most troubles and most possibilities for improvement add up to proportions something like this: 94% belong to the system (responsibility of management), 6% special.[4]

His point in saying this is that a tiny fraction of an organization’s overall performance problems, the 6% special, can be attributed to individual performance issues. Instead, most of the causes of failure lie in how we organize the work we ask people to carry out. Deming taught us that improving quality in complex systems is not principally about individual competence, but rather about designing better systems.

When viewing the middle school through the lens of the organizational chart in Figure 1, that is hard to comprehend because all that you see is the individual workers. When viewing the system in which the middle school sits as displayed in Figure 2, the view is far more revealing. The system is not only made up of the administrators and teachers within the school building, but it also includes students and their families and the communities in which they live. It includes higher education as both a customer as well as a supplier of educators. It includes government and the resources it supplies to both the school as well as the community in which it is situated. The government also sets policies for the school such as state learning standards and tests. All of these are components of the system, and if you follow the arrows around the diagram beginning with the school you start to appreciate the complexity. Following the arrows around the diagram beginning with the school and moving to the right, then up, then left, and finally back down to the school you see that the systems view also forms a feedback loop from which to learn. Viewed in this way, not only are there significantly more individual components to consider in the systems view, but there is also the interaction of these components that is important. Systems thinking expert Dr. Russell Ackoff put it this way:

A system is never the sum of its parts; it’s the product of their interaction. The performance of a system doesn’t depend on how the parts perform taken separately, it depends on how they perform together – how they interact, not on how they act, taken separately. Therefore, when you improve the performance of a part of a system taken separately, you can destroy the system.[5]

When the individual educators, organizational components, and the interactions between both the individuals and those components are considered, the idea that the system accounts for the vast majority of the variation in the outcomes we see in schools becomes much clearer.[6] To be sure, there is a very small number of educators that do not belong in front of a classroom or leading a school building or district. However, most of the potential to eliminate poor performance in schools lies with improving the systems and processes through which work is done, not in changing the individual educators. Even in situations where it appears that an individual has done something wrong, the root of the problem often can be traced back to how that employee was trained, which is itself a type of systems problem. Once leaders recognize that systems create most of the problems, we can stop blaming individual educators and instead ask, “What in the system needs improvement?”[7]

Understanding Profound Knowledge

In this post, I introduced the idea of Appreciation for a System. In the subsequent summer months and into the early fall, I’ll provide an overview of the other three components of the System of Profound Knowledge and examples for how the theory can be applied in schools. August’s post will focus on Knowledge about Variation, September’s post will focus on Theory of Knowledge, and October’s post will focus on Psychology.

For additional information on how United Schools Network is applying the ideas discussed in this article, you can check out recent interviews on the Lean Blog Interviews Podcast and on the Connecting the Dots podcast.

***

John A. Dues is the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus, Ohio. Send feedback to jdues@unitedschoolsnetwork.org.

Notes

[1] Anthony S. Bryk, Louis M, Gomez, Alicia Grunow, and Paul G. LeMahieu, Learning to Improve: How America’s Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2015), 198.

[2] TNTP. “The Mirage: Confronting the Hard Truth About Our Quest for Teacher Development.” 4 August 2015, https://tntp.org/publications/view/the-mirage-confronting-the-truth-about-our-quest-for-teacher-development.

[3] W. Edwards Deming, The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education, 3rd ed. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018), 39.

[4] W. Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis. (Cambridge, MA: MIT, Center for Advanced Engineering Study, 1986), 315.

[5] The Deming Cooperative. “2003 Ackoff Seminar Part 1 of 4.” YouTube, 1 July 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a0ooqJ-pOH4&t=366s&ab_channel=TheDemingCooperative.

[6] Joseph Juran estimated this to be 85% system and 15% individual while Deming attributed up to 98% of the performance variance to the system, depending on the situation.

[7] Peter R. Scholtes, Brian L. Joiner, and Barbara J. Streibel, The Team Handbook, 3rd ed. (Edison, NJ: Oriel STAT A MATRIX, 2010).