Principle 12: Remove Barriers to Joy in Work & Learning

Common management myths (see here and here) must be replaced by sound guiding principles. In this post, I’ll describe the twelfth such principle, Remove Barriers to Joy in Work & Learning.

It is worth noting that the 14 Principles for Educational Systems Transformation are mutually supporting, so it is important to understand all of them rather than studying them in isolation. An in-depth discussion of the full set of Principles for Transformation can be found in Chapter 3 of my recently released book Win-Win: W. Edwards Deming, the System of Profound Knowledge, and the Science of Improving Schools

Principle 12: Remove barriers that rob educators and students of their right to joy in work and learning. This means, inter alia, working to abolish the system of grading student performance, the annual or merit rating of staff, and the Management by Objective of schools and school systems. The responsibility of all educational leaders must change from sheer numbers to quality.

The unifying theme of Principle 12 is the concern with pride of workmanship, what I call “Joy in Work” and “Joy in Learning” throughout my aforementioned book. Barriers against the realization of Joy in Work and Joy in Learning may be one of the most important obstacles to improvement of the quality of our educational systems in the United States. These barriers must be removed at three levels of our educational system. One level is students where the barrier is the system of grading student performance and the ratings and rankings that are a by-product of the grading system. A second level is teachers, principals, and other educators where the barrier is the annual rating of performance or merit rating, especially teacher and principal performance appraisals that include student test data as a part of the rating system. The third level is the grading, rating, and ranking of schools and school districts within public school accountability systems. There is a common problem with the grading and rating systems at all three levels. That is, they involve the judgment and ranking of people, while failing to recognize that most of the variation in performance comes from the system within which the people live, learn, and work rather than from the people themselves.

Deming has indicted the system of reward as being one of the main constraints holding us back from a Win-Win culture. Grades at all three levels of the education system – the grading of students, the grading of educators, and the grading of educational institutions – are reward systems. In Chapter 2 of Win-Win, I spend considerable time discussing the Myth of Performance Appraisal as well as the Myth of Merit Pay, which both have to do with rating and ranking educators. In Principle 3, I outlined some of the most important problems with grading students. In addition to those previously mentioned problems, I’ll add the Pygmalion Effect to the list.

In one landmark study documenting this powerful effect, teachers were told by researchers that certain students in their classes had performed well on a test that predicts intellectual growth. In truth, these students had been randomly selected by the researchers to be described as high performing for the purposes of the experiment. These students were in fact only distinguished by their teachers’ expectations for their performance. Eight months later, those randomly selected students described to the teachers as high performing had significantly outperformed their peers on IQ tests. And the teachers themselves consistently described the “bloomer” students as better behaved, more academically curious, more likely to succeed, and more friendly than other students in the class.[1] The Pygmalion Effect coupled with the issues of grading from Principle 3 should leave us with serious concerns for student grading systems.

State accountability systems have extended the grading, rating, and ranking from individual students and educators to schools and school systems. As previously discussed on this blog, schools and school systems in Ohio receive report cards with an overall grade as well as grades in various performance categories. What are school report card grades measuring exactly? Are those grades a fair representation of the activities occurring within the school? Or can a significant portion of those grades be attributed to the larger context in which a school sits? Systems thinking assigns most differences in school performance to the system and not to individual schools.

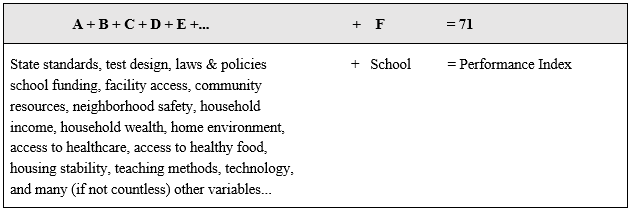

One way to consider the theory behind the systems thinking perspective is to try to solve the equation below for the Performance Index component of Ohio’s school report card. The Performance Index (PI) is a measure of the test results of every student and is reported as a numerical value with a top score of 120.

If A + B + C + D + E + F = 71 (PI score), what is the numerical value of F?

Obviously, the equation cannot be solved without knowing the values of A through E, or at least their sum. However, the report card system in Ohio suggests that we can assign a value to F (the school) with no knowledge of the values or effects of the other variables. The accountability system accomplishes this impossible task as follows:

Table 1. An Impossible Equation

As systems leaders, instead of developing ever more complex systems for grading, rating, and ranking students, educators, and schools, we instead should shift to figuring out how to remove barriers to Joy in Work and Learning. This will help put us on the path to transforming those systems.

Blog Series: 14 Principles for Educational Systems Transformation

The four components of the System of Profound Knowledge work in concert to provide us with profound insights about how our organizations operate so that leaders can in turn work to optimize the whole of our systems. However, there is a step beyond simply avoiding the management myths. The next step is to be able to think and make decisions using the lens provided by the System of Profound Knowledge. This is where the core set of 14 Principles come into play. In this series, I’m describing the principles that will enable you to move from theory to practice with the Deming philosophy.

***

John A. Dues is the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus, Ohio. He is also the author of the newly released book Win-Win: W. Edwards Deming, the System of Profound Knowledge, and the Science of Improving Schools. Send feedback to jdues@unitedschoolsnetwork.org.

Notes

As described in: Steven Farr, Teaching as Leadership: The Highly Effective Teacher’s Guide to Closing the Achievement Gap (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010), 26-27.