Systems Must Have an Aim

Note: The aim of this nine-part series is to define and describe the basic structure and components of a system. This is the second post in the series, which is excerpted from Chapter 4 of my recently published book, Win-Win: W. Edwards Deming, the System of Profound Knowledge, and the Science of Improving Schools.

In a general sense, a system is “a set of elements or parts that is coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors, often classified as its ‘function’ or ‘purpose’."[1] Most typically, when I refer to a system in Win-Win I am referring to an organization (e.g., United Schools Network). Thus, a useful definition of a system is “an organization characterized by a set of interactions among the people who work there, the tools and materials they have at their disposal, and the processes through which these people and resources join together to accomplish its work.”[2]

The aim of a system is a qualitative statement with methods attached that detail its long-term constancy of purpose. Dr. Deming taught us the following about the aim of a system:

A system must have an aim. Without an aim, there is no system. The aim of the system must be clear to everyone in the system. The aim must include plans for the future. The aim is a value judgment. The secret is cooperation between components toward the aim of the organization. We cannot afford the destructive effect of competition.[3]

It will be helpful here to start with some characteristics of an aim statement in terms of what it is and what it isn’t. The bulleted lists in both categories that follow come from a careful study of Deming’s writing about the aim of a system.

What it is:

Long-term constancy of purpose

Value judgment/clarifies values

Relates to a better life for everyone

Purpose with a method attached

Includes the future

Aspirational

Precedes the organizational system

Guides behavior

Everyone must understand it

Tied to and guides the system

Transcends individual preferences; group calling

Cooperative in nature

Focused on the whole organization

Set by leadership

Coordinates efforts

What it isn’t:

Not a specific activity or method

Not a numerical goal

Not tied to a specific outcome

Not Management by Results or Objective

Not a way to control or punish

Not a product of external pressure

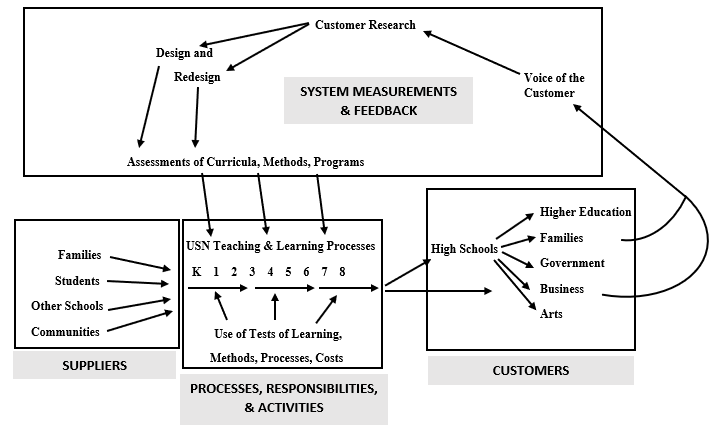

In Figure 1 below, four components of the systems view have been labeled and appear in the black boxes. Those four components include (1) Suppliers, (2) Processes, Responsibilities, & Activities, (3) Customers, and (4) System Measurements and Feedback.

Figure 1. Systems View

Suppliers are the inputs to the system. In the case of schools, this includes the families, other school districts, and communities from which students come. The processes, responsibilities, and activities are the throughputs in the system. In schools, these largely are made up of the teaching and learning processes that take place in classrooms. The customers receive the outputs from the system. Families are customers of the school system, but so are high schools (USN is a K-8 system) and other parts of society such as the business and arts sectors. The fourth and final component is the system measurements and feedback that inform the design and redesign of the school system.

More attention will be paid to these components in future posts, especially regarding the role of students, teachers, building administrators, system leaders, and board members. For now, this introduction to the four components will suffice; the purpose of gaining an understanding of the systems view is focused on the following question: What is the aim that provides purpose and direction to the system? By now, the importance of a clearly defined aim to guide the system and all its components should be clear. An organization must have an aim to ensure that everyone across all four components of the system is moving in the same direction.

Next month, we’ll take a look at how we went about adding an aim statement to the vision and mission statements we already had in place to guide our work at United Schools Network.

***

John A. Dues is the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus, Ohio. He is also the author of the newly released book Win-Win: W. Edwards Deming, the System of Profound Knowledge, and the Science of Improving Schools. Send feedback to jdues@unitedschoolsnetwork.org.

Notes

Donella H. Meadows, Thinking in Systems: A Primer (White River Junction Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008), 188.

Anthony S. Bryk, Louis M, Gomez, Alicia Grunow, and Paul G. LeMahieu, Learning to Improve: How America’s Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2015), 198.

W. Edwards Deming, The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education,3rd ed. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018), 29, 36.