Knowledge has temporal spread

Note: This is Part IV in a five-part series on W. Edwards Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge, which covers the Theory of Knowledge. It may be helpful to read Part II: What is systems thinking? and Part III: Variation is the enemy prior to this post.

Knowledge has temporal spread.

Understanding these four words is critical to the understanding of the third component of the System of Profound Knowledge - Theory of Knowledge. In describing this component in The New Economics, Deming put it this way:

The theory of knowledge helps us to understand that management in any form is prediction. The theory of knowledge teaches us that a statement, if it conveys knowledge, predicts future outcome, with risk of being wrong, and that it fits without failure observations of the past. Rational prediction requires theory and builds knowledge through systematic revision and extension of theory based on comparison of prediction with observation.

In our organizations, theory must be the basis of all investigation, and the basis for any action we take to improve systems within our organizations has to include testing our theories. The Theory of Knowledge is all about where our knowledge comes from that we use in these improvement efforts. This knowledge has temporal spread. Meaning information in the form of data is constantly streaming in at us over time. This information becomes knowledge when we can articulate a theory for the data we are seeing and can predict how that data will perform over time. That’s what Deming meant when he said that management in any form is prediction.

Enumerative vs. Analytic Studies

Core to the Theory of Knowledge is the importance of understanding how people think and act, based on what they believe they know to be true. Here it is important to highlight a distinction that Deming made between enumerative studies and analytic problems. He often drew the analogy that enumerative studies are akin to sampling water from a pond similar to what happens during the Census. The Census is an enumerative study that produces information about the population of the United States at a given point in time. On the other hand, organizational leaders are concerned with analytic problems that function much more like a stream rushing down the side of a mountain. The 8th grade math engagement data discussed in my last post functions much more like the mountain stream than it does a pond. We are getting daily updates to this “stream” of data and what is most important to us is understanding how a specific change in process or procedure impacts this data.

Applying the Theory of Knowledge

The most important questions that follow from the application of the Theory of Knowledge is How do we know what we know? and Why do we do things the way we do them? If you reflect on those questions in your own work you may be surprised where those answers lead, even as you examine well-established policies, processes, and practices within your organization. For example, consider the instructional methods at your school. What is the underlying theory for those methods? Does the theory align with the best of what we know about memory and cognitive psychology? Is there a book or perhaps a consultant that helped inform those practices? Or, perhaps no one really knows the answers to those questions. It can be a bit daunting to begin to ask these questions because they often lead to uncertain answers. However, they are important questions to ask and even if the answers cause anxiety at the onset, they are the first step on a journey to grounding our work in better theory.

As we consider the way in which we typically evaluate ideas, it is not based on the cold logic we may like to believe it is. There is a danger here that very little thinking or evaluation is going on at all in schools as we see many education leaders hop from fad-to-fad in their attempt to find silver bullet improvement ideas with little basis for these choices. Assuming this is not the case in your organization, there are still biases we have to overcome as we evaluate ideas for improvement. For example, we often evaluate ideas from people we like more favorably than those with whom we don’t like rather than evaluating the idea on merit alone. As decision-makers, we are also very susceptible to confirmation bias which means that we tend to latch onto evidence that supports our beliefs and ignore evidence that undermines those same beliefs. In order to more effectively adjust our beliefs to reality we are well served to question whether we are falling for these biases.

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Cycles

One of the most powerful tools that sits at the heart of Deming’s Theory of Knowledge is the Plan-Do-Act-Study (PDSA) cycle. PDSA cycles are experiments during which you gather evidence to test your theories. Observed outcomes are compared to predictions and the differences between the two become the learning that drives decisions about next steps with your theory. The know-how generated through each successive PDSA cycle ultimately becomes the practice-based evidence that demonstrates that some process, tool, or modified staff role or relationship works effectively under a variety of conditions and that quality outcomes will reliably ensue within your organization.

This is a key differentiator of PDSAs as a learning process as compared to using ideas generated through traditional research methods, even gold standard methods such as randomized controlled trials. By their very design, studies that result in evidence-based practices discount externalities instead of solving for them. This is not helpful for educators working in real schools and classrooms. The idea that many interventions are effective in some places but almost none of them work everywhere is such a common idea in the education research sector that this phenomenon has its own name- effects heterogeneity.

Beyond the concern of effects heterogeneity, there are a number of other reasons the PDSA is an effective tool. People learn better when they make predictions as a part of the process because making a prediction during the planning phase of the PDSA forces us to think ahead about the outcomes. In my experience, we are often overly optimistic in terms of both the speed and magnitude at which improvement will occur. But, because making a prediction causes us to examine more deeply the system, question, or theory we have in mind as we develop change ideas, we both get to see the thinking process of our team members as well as improve at making predictions over time. Learning about your ability to predict in addition to your organization’s ability to predict is a key part of the Theory of Knowledge.

Theory of Knowledge in Action

As previously mentioned, theory must be the basis of all investigation, and any action we take to improve systems within our organizations has to include testing our theories. Here it is important to differentiate between information and knowledge. Figure 1 illustrates the 8th grade math engagement data for the first 24 days of the school year that I examined in my last post. We have pieces of information such as the fact that on average 67% of students complete the daily lesson activity. We also have information about the daily engagement rates for these 24 days of remote learning. For example, on Day 7 only 58% of students completed the lesson activity, whereas 81% were engaged on Day 18. This data information, however, is not knowledge. Knowledge is the analysis and interpretation of this informational data that leads us to be able to predict system performance. In other words, we don’t have knowledge about the 8th grade math system until we have the ability to predict how the engagement rates will perform over time. In turn, we have to have the ability to predict system behavior before we can work on improving the engagement rates of the students within that system.

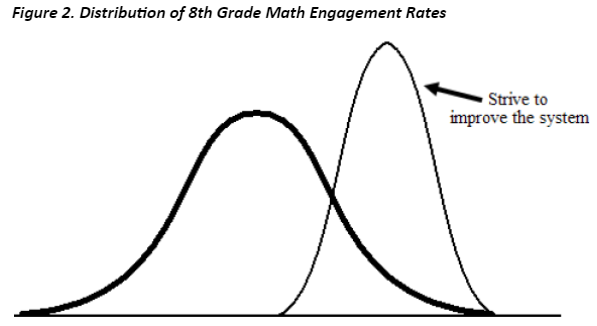

Everything we are doing in schools really comes down to improving quality. By quality I mean minimal variation around a target value. Quality improvement work then is focused on reducing variation around that target value. I not only want to raise the average engagement rate in 8th grade math, I also want to reduce the variation around the target as I move the distribution of the rates to the right as depicted in Figure 2. This idea of moving the distribution to the right and reducing the variation around the target is the central point of the idea that variation is the enemy.

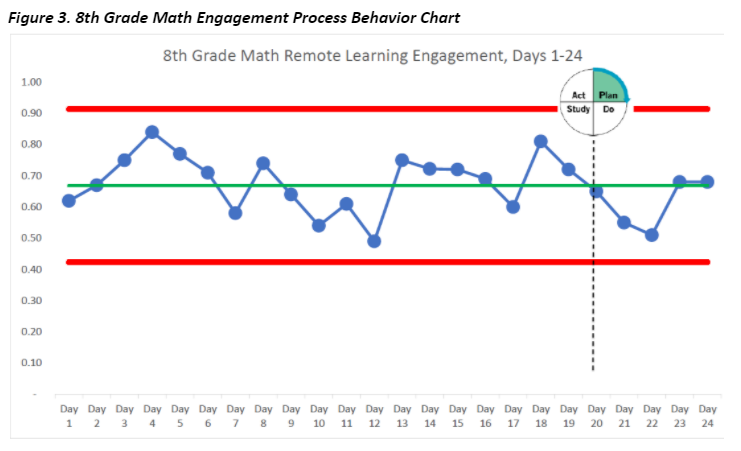

If we take that data from the table in Figure 1 and place it in a time-sequenced chart, we can then start to better understand how the 8th grade math system is functioning. Plotting the dots, that is the daily engagement rates, as I’ve done in Figure 3 is part of what Deming meant when he said that knowledge has temporal spread. Each cell of the table in Figure 1 is like taking that water sample from the pond, but that is not how data that we care about comes to us in real life. The problem with the table from Figure 1 is that the display is static; it doesn’t give me a sense of how the data is changing over time. Most of the data we care about in schools rushes in at us in a continuous fashion like a mountain stream; it’s dynamic data. The process behavior chart (see the linked article for more technical information on this tool) in Figure 3 allows me to see what that stream of data looks like over time. That is the picture of the remote learning system that I need in order to do true quality improvement work.

Once I have plotted enough points, I start to have a lens through which to view this new remote learning system. We all likely would agree that our 8th grade math system is not producing the types of engagement that we would like. Deming’s Theory of Knowledge offers a way forward. This is represented by the vertical dotted line and the PDSA icon on the process behavior chart. At the point that the team recognizes that there is a need to improve remote learning engagement levels, we can then work together to design and test a change idea through PDSA cycles. The purpose of this experiment is to provide a structured approach to improvement where a change idea is systematically tested to see if it in fact brings about improved rates of engagement. By monitoring the daily engagement levels after the PDSA is started, the team can then determine if the intervention is effective. If it is effective, we’ll start to spread it to more students. If it’s not, at least we learned that it was ineffective prior to implementing it far and wide and with great expense.

In the world of education reform, we do the antithesis to the PDSA cycle. We go fast, learn slow, and fail to appreciate what it actually takes to make promising ideas work in practice. These efforts are far too often not grounded in theory. And, as Deming stated so clearly:

Without theory, one has no questions to ask. Hence without theory, there is no learning.

Indeed.

***

John A. Dues is the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter-management organization that supports four public charter schools in Columbus. Send feedback to jdues@unitedschoolsnetwork.org.